Strange & Fantastic #22

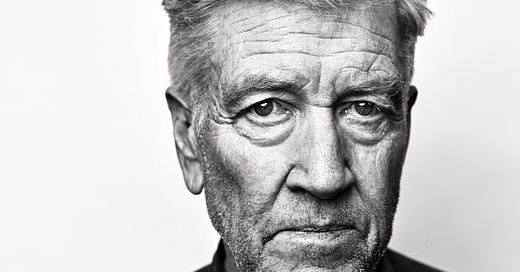

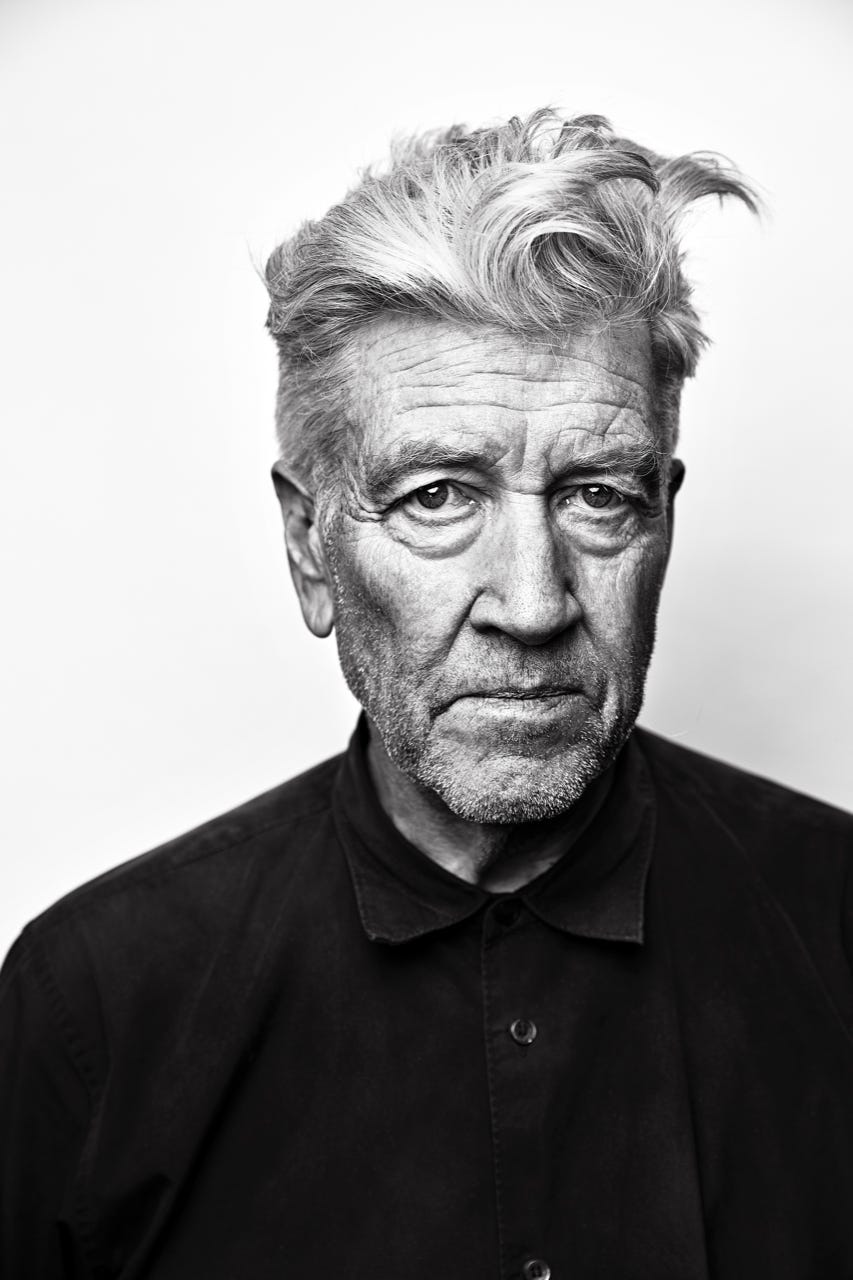

Some thoughts on the passing of David Lynch, plus Mushrooms for Mirabelle Part 3

Hey there, and welcome to the first newsletter of 2025! I hope everyone had a wonderful holiday season with family and friends—I know I did! It was busy, but great nonetheless.

I’ve been thinking about director and artist David Lynch a lot since the news broke of his passing on January 15, 2025. I came to the majority of Lynch’s work later in life (within the last two years or so, despite having been interested in Lynch and his work since my teens), and since then he and his films have come to mean a lot to me: no one else, in my mind, can marry the mundane and the surreal, the horrific and the quaint (and the funny!), quite like David Lynch can.

Most of all, the way Lynch approached creativity has been a huge inspiration to me of late. His mantra was to be open to any and all ideas, to follow the ideas where they might take him—he didn’t try to figure them out or place them in the confines of what he thought whatever story he was working on should be, but let the ideas themselves lead. Lynch was an artist who trusted his ideas. This creative free-flow was a massive part of Lynch’s life, and I’m convinced it’s what made his work so special and singular.

I encourage anyone engaged in any creative endeavor (or anyone interested in Lynch and his work) to check out the books Lynch on Lynch and Room to Dream, as they both go into great detail regarding Lynch’s art life. (I started listening to the audiobook of Room to Dream the day after Lynch passed and was excited to find that he narrates whole sections of the book himself; there’s something comforting about still being able to hear his distinctive voice after he’s passed on.)

And if you haven’t checked out any of Lynch’s work (he directed films, painted, recorded music, and wrote books), there’s no time like the present. Might I suggest starting with Twin Peaks? It’s not only my all-time favorite work of his, but probably his most newcomer-friendly. (I will die on the hill that Twin Peaks is the greatest TV show ever; I actually had started rewatching the series a week before Lynch passed—a twist of fate would not have been lost on Lynch.)

So, all that to say: Rest in Peace, Mr. Lynch—and thanks for all the amazing work you left behind for us to enjoy, contemplate, and be inspired by for many ages to come.

Monthly Serial: Mushrooms for Mirabelle

(Part 3)

Granny Bigelow’s homestead wasn’t really a house—it was more a pile of old wood and stone topped by a moldering thatch roof. It loomed dark and lonely on the outskirts of town, on the edge of the Wytchwood. Looking at Granny’s place, I could understand why everyone reckoned her a witch: even her home looked the part. But then, our house didn’t look much better.

Mayhap things ain’t always what they seem, Mirabelle thought, as we approached Granny’s door. Sometimes she’d forget I could hear her thinking just as well as I could hear her talking.

Mayhap they’re exactly what they seem, I said.

“I told you, stop listening to my thoughts,” Mirabelle said.

And I told you, I can’t help it.

Mirabelle huffed and raised her hand to knock on Granny’s door, then hesitated.

Even after Granny had left the roast rabbit on our doorstep that first night, and after she’d come again every night after that, leaving food on our porch, Mirabelle still wasn’t sure of the old woman. Neither of us were. It’s hard getting past things you learn as a kid, especially the prejudices taught as gospel truth. Eventually, though, the roast rabbit, the venison stew, and the cooked ground-birds won out.

Granny had kept my sister and daddy and brother from starving to death.

“She’s our last hope,” Mirabelle said, as much to me as herself.

She knocked.

The door creaked open on rusted hinges and there was Granny, peering out from the dim space between the door and the frame. Fire flickered behind her, outlining her in orange and yellow. She smiled.

“Well now,” Granny said, waving Mirabelle inside. “Been hoping you come on by.”

She shut the door behind us.

Inside, Granny’s home was as old and dark as it was outside. The only light besides what came from the fireplace at the back of the room came in through a dirty window at the other side of the house. Bunches of plants lined the sill, with more arranged in the dirt beneath it. They looked like weeds, mostly—not the kinds of plants someone would keep watered and healthy, especially inside their home. Against the other wall, behind a circular wooden table with three legs propped up by pieces of broken shale, sat a dirty mattress topped with a raggedy blanket.

I heard a skittering sound, like tiny nails clawing dirt, and then a black, plump shape hidden among the plants startled and bolted past the fireplace, disappearing into a hole in a far corner behind Granny. It looked like it might’ve been a rat, but I wasn’t sure. Guess maybe my being there spooked it.

Granny made no sign that she’d noticed the critter. Instead, she hobbled over to the fire, stirred whatever was boiling in the pot there, then moved to the table and sat in one of the two chairs. She motioned Mirabelle over.

My belly started feeling sick again, and it got worse anytime I focused on the black oil shimmering around Granny.

Belle, I said, as Mirabelle sat herself at the table across from the old woman, we really shouldn’t—

“Now, now,” Granny said, looking right at me, pinning me to the door with her gaze. “No need to be afeared, my boy.”

Mirabelle stiffened. “You can—”

Granny nodded.

“I thought I were the only one,” Mirabelle said.

Granny waved me over to the table. “I ain’t mean you or your darling sister no harm, child. You’re safe with ol’ Granny. Promise.”

I shook my head and clenched my jaw shut. There was no way I was going anywhere near that woman, especially now that I knew she could see and hear haints.

Granny sighed.

“Sorry about him,” Mirabelle said. “He just protective, is all. And he ain’t met no one but me as can see or hear him.”

“Oh, I understand,” Granny said, smiling at me. The smile made me feel cold-like. Well, colder than normal; I was always feeling cold. She turned her attention back to Mirabelle. “Did you enjoy the food, dearie?”

“Yes’m,” Mirabelle said. “But why’d you do that? Why now?”

“How d’you mean?” Granny said. “You was hungry, so I brung you food.”

Mirabelle shook her head. “No, I know that. I meant how come you brung us food now, but never before? All them other times we was starving. Why d’you care now, all out of the blue?”

“Aw, honey, it ain’t like that. I ain’t never seen you before, is all. Not til that day out in the ‘Wood. I hear about your family, sure, but I hear lotsa things. Can’t believe it all. And since I ain’t never seen you or your family, at least up close, I never knew what y’all were going through. Soon as I seen you in the ‘Wood, seen you underfed and starving, well, I reckoned there must be some truth to what I hear, and I reckoned you need some help. And when you act so scared of me, well, I reckoned I better make clear I only means you good.”

Mirabelle sobbed like a baby. I was about to move from the door, but Granny got up from her chair, knelt before Mirabelle, and pulled her into her arms. Mirabelle just cried harder and louder with Granny’s arms around her.

“Aw, now, honey,” Granny whispered. “Aw, now, baby girl. It’s okay, now. Granny got you. Just you cry, child. Just you cry. Granny got you. Granny got you now.”

Belle, I said, aching something fierce to reach out and hug my sister, but a look from Granny froze me in place.

After a while, Mirabelle’s crying became sniffling and she stopped shaking. Granny pulled back and wiped hair from Mirabelle’s face, leaving dark smudges from her dirty fingers. I worried some of her oily shimmer might get on Mirabelle, but I reckon it don’t work like that.

“Now, child,” Granny said. “What say you tell ol’ Granny your story while she fix us some supper, huh?”

“What story?” Mirabelle asked.

“Your story,” Granny said. “You and your family’s. I only hear what the townfolk say, and Lord know if that true. I wanna hear you tell it, in your own words. The truth, dearie.”

“The truth?”

Granny nodded and got to her feet. She turned to the pot and ladled stew into two earthenware bowls she kept stacked in the dirt next to the fireplace. With her back turned, I finally got up the courage to join Mirabelle. I hovered behind her chair, peering over her shoulder, always eyeing Granny.

Granny returned, placed two steaming bowls of stew on the table, and sat down.

Belle, I said. Don’t—

“Shush,” Mirabelle said. She took a deep breath, and told Granny our story.

***

It all happened after Mirabelle turned thirteen.

The week after her birthday, Daddy had the accident in the mines that left him crippled, scarred, and in excruciating pain.

Six months after that, Mama lost her mind. She drowned baby Florabelle in a washbucket, slit my throat when I tried to stop her, then hung herself in the Wytchwood by her own apron; I was only eleven and three-quarter years old. I don’t rightly know why Mama only went after me and Florabelle; I reckon maybe she figured Mirabelle and Henry were old enough to hold her off, mayhap overcome her. Mayhap they were her favorites, I don’t know.

I try not to think on it much, truth be told.

I can tell you though, dying was mighty strange. Suddenly you’re there, then you’re not, then you’re wandering through the hills and woods, only a shadow of yourself, solid things passing through you like you’re nothing but a cloud, then you’re falling through the ground or floating above it, always floating. No sense of direction or smell or touch, head full of jumbled thoughts and hazy, half-remembered memories. It took me a good, long while to find my way back home, back to Mirabelle.

Before I returned home, and after Mama went crazy, Henry—he’d been working in the mines in Daddy’s place—up and disappeared. Search parties looked all over for him beneath the mountain, but they didn’t find any sign of him. Three weeks later, he showed up in his old bedroom, rocking back and forth with spikes of coal driven into his ears. He’d stabbed himself deaf, and he ain’t never uttered a word since.

By the time Mirabelle was fourteen, our neighbors had all left for the Granger Mining Co. houses on North Street, afraid that whatever curse had stricken our family would spread to theirs next. The Wests and the Seeleys, the neighbors on either side of our house and the ones we always reckoned as extended family, were the first to leave. I think that just about killed Mirabelle.

In time, our house was the only one left haunting Old East Street. Weeds and vines, insects and vermin, they replaced our neighbors. The house began falling apart, our family’s misfortune writ large in rotting wood.

No one helped Mirabelle. If they saw her around town, they’d just treat her like a leper, a pariah.

No one cared about the Cranes no more.

TO BE CONTINUED…

Signing Off

That’s it for January 2025.

As always, thanks so much for reading, and stay strange. (Now, seriously, go watch Twin Peaks!)

—Austin

If you enjoyed this newsletter, please subscribe—you’ll get a free eBook of my short story, “Magus,” available EXCLUSIVELY for subscribers!

I’d also love it if you considered checking out my weird fantasy noir novella, City of Spores, or my illustrated sci-fi thriller chapbook, Goodly Creatures.